Americans go to the Netherlands for all kinds of reasons. They stop there on magnificent cruises. They see priceless art at the Van Gogh Museum. They dive into WWII history at the Anne Frank House or the Bridge Too Far. Some come for the – let’s call it “cultural freedom” – of Amsterdam. Most do not come to see the Amsterdam courthouse, and even fewer come to participate in legal proceedings there. But I’m not most people.

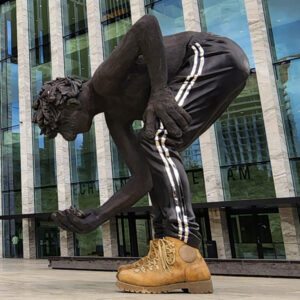

In a city known for unique architecture, the 10-story New Amsterdam Courthouse is surprisingly normal. From the outside, that is, unless you consider the bizarre statue in front.

Sculpted by American artist Nicole Eisenman, “Love or Generosity” depicts a guard – wearing only work boots and sweatpants – holding an owl, an acorn, and an arrow. I’m told the friendly five-meter “gatekeeper” is meant to put visitors at ease and evoke curiosity. Like Alice through the rabbit hole, things are about to get curiouser and curiouser.

Inside, I pass through a metal detector supervised by guards who are actually wearing shirts. They inspect my backpack and give me the nod to rejoin my lawyers, my advocaats, as they are called in the Netherlands. We ascend three sets of escalators and arrive at courtroom F6, which I note is also the MUTE button on my laptop. I hope it’s not an omen.

Advocaats for both sides wait in the hallway, tension thick as they slip black robes over their business suits. The robes are adorned with long white cravats, ruffled like tuxedo shirts, with strings that tie at the back of the neck like Halloween costumes. I wonder if the judge will be wearing a cool white wig like George Washington.

“Loop the rubber strap over your ear with the button facing in,” says the Dutch-to-English translator as she hands me a device that looks like a 4th generation iPod Shuffle (the little square one I never liked). This one, however, I like very much. She tests her microphone as we enter the courtroom, where the judge and the court clerk are both seated behind the bench. Neither of them have wigs, or if they do, they’re really good ones like William Shatner’s.

Representing my employer defending against a hostile takeover, I sit next to my three advocaats. Unfortunately, the desk is too small for all of us, and I’m forced to sit out in the open with a spiral notebook on my lap, totally exposed and vulnerable. Wonderful.

Unlike American court proceedings where silver-tongued lawyers grill witnesses on the stand to achieve “gotcha” moments like Perry Mason or Boston Legal, the Dutch proceedings are surprisingly choreographed. Advocaats for the plaintiffs hand out packets to everyone, including me. I don’t know if it’s procedure or courtesy, but I’m pleased to be part of the action. Then I look at all the Dutch words, with an occasional Latin phrase or English quote from a United States court ruling inserted as evidence, and I wonder why they wasted the paper (I don’t think I’m breaking any news here; I don’t speak or read Dutch).

“That’s the text of their argument,” the translator whispers in my ear.

And so it begins. Instead of passionate arguments, the advocaats proceed to READ their pages, word for word. As the judge follows along with his own copy, I listen to Dutch in my right ear while the translator whispers nearly real-time English in my left. I hope she’s accurate and not just winging it.

There’s no choice but to trust her, even though she suddenly seems to be translating from the future. The plaintiff’s advocaat quotes a long passage from an American court ruling. I can follow the script since the quote is in English, and I can understand the words in my right ear for a change. No problem. Except… the translated words in my left ear are coming BEFORE the words floating in the air around me.

Are the words of opposing counsel falling into a time vortex that allows the translator to hear them before anyone else in the room? That’s awesome! As I look back at her, I realize she’s just translating the script at a speed that seems natural to her, unaware she has outpaced the speaker. Weird.

I feel like a fish out of water having an out-of-body experience. Then the quote is over, the Dutch resumes, and I return to my new normal.

For 30 minutes there are no ad-libs, no Perry Mason moments, just a dry reading of prepared arguments. The judge asks a few clarifying questions, which are nicely translated along with the lies told by opposing counsel. Then it’s our turn.

My advocaats hand out their own packets, but because they like me, I get my very own English version.

“You can follow along with your copy,” the translator whispers in my ear. Easy for you to say, I think as my advocaats begin their own reading, word for word – in Dutch. I look for recognizable words and sounds as we move through 100 paragraphs on 12 single-spaced pages. Ah, “Delaware Supreme Court” – we must be at paragraph 1.2(f). “Ultra-D Technology demonstrator samples” – sounds like paragraph 3.5(a).

Where is the voice keeping me grounded in this strange land? For 30 minutes, she whispers nothing. Finally, she says something that is not in my script: “Mr. Robertson would like to add some comments of his own if the court will allow.”

I’m on. The judge focuses his attention on me. I’m the only one without a desk or robe to hide behind. No sprachen ze Dutch comes to mind, but I doubt it will get me out of the spotlight. I’d make a run for it, but my passport is back at the hotel. Nothing to do now but complete the job I’ve come to do. I hope the judge’s English is better than my Dutch.

I summarize three years of litigation and the underlying civil conspiracy against us. Everyone listens politely, unaware that I’m stealing sideways glances to make sure opposing counsel isn’t about to throw blunt objects at me. Realizing that there’s no bailiff in the courtroom to take my attackers down, I try to remember a YouTube video describing 21 ways to defend yourself with a ballpoint pen.

The judge asks me a few clarifying questions, then offers each set of advocaats a chance to rebut the presentations of the other. The moment I’ve been waiting for is finally here: legal jousting, witty banter, tactical maneuvering, and eventually, my lawyers doing a victory dance atop the scattered bodies of our enemies.

Every unscripted word that follows is in Dutch, and the translator really earns her money as she keeps pace with arguments, questions, and answers that continue for at least an hour. At some point I become comfortable hearing two different languages simultaneously, like reading English subtitles while watching a foreign film, and I’m sucked into the proceedings as deep as any television show I’ve ever seen.

And then it’s over. No carnage, no shouting, not even a shoe thrown for good measure.

Outside the courtroom, advocaats from both sides remove their robes and cravats, stuffing them back into bulging briefcases. Now that they’re once again just normal guys in expensive suits, they shake hands and smile, as if they’ll be seeing each other soon at social functions. I’m sure they will.

I leave the building both disappointed and relieved that the proceedings have gone without violent outbursts. The verdict, if we lose, will be painful enough.

At the airport, I see one final omen. I’m tempted to try my hand at Dutch, but that’s not my thing…